While the HAA is perhaps best associated with high-octane ‘warbirds’ a number of members have aircraft which are a little more modest. One such was an aeroplane which was already an anachronism when became was the subject of a book written more than 50 years ago, but it inspired many to take up flying; Currie Wot G-APNT, better known as “Airymouse”.

Today, Airymouse is owned by Light Aircraft Association CEO Steve Slater who, given its history, describes himself as “its custodian”. Steve gets us up to date on Airymouse’s story.

CALL IT WOT BLOOMING WELL YOU LIKE.

Airymouse wasn’t the first Wot to be built. That honour goes to two examples which were built pre-war by Joe Currie at Cinque Ports Aero Club in Kent. Joe had flown SE-5As during the Great War and became a lecturer at Chelsea College in London. In 1936 he drew up the design as a project for his students and when construction started, passers-by inevitably asked “what” they were building. Joe’s gruff response was “you can call it wot you blooming well like”. The name stuck!

Joe Currie in the Wot 1958

The Wot stuck to what Currie was familiar with; effectively a smaller version of the famed SE-5A fighter (so it’s no surprise that many 7/8-scale replicas have been built on the basis of Currie Wot drawings), all-wood with fittings hand-made from mild steel plate. The result was a compact biplane, with a wingspan of a tad over 22 feet. Concessions to cost and weight saving included ailerons on the lower wings only, unstreamlined bracing wires, a simple bungee suspension undercarriage, a fixed tailskid and no brakes (more on that later!).

Airymouse just before first flight

Both original Wots apparently flew well, although utilisation was somewhat limited by the fact that the two aircraft had just a single engine shared between them, a 36hp flat-twin which had been salvaged from an Aeronca C2 which had been crashed by Roger Bushell, who later as a PoW went on to be executed as the leader of “The Great Escape”. The two aircraft also suffered Nazi atrocity, they were destroyed by Stuka dive bombers in an air raid on Lympne in May 1940.

During WW2 Joe became an RAF Engineering Officer, before a heart condition saw his return to civilian engineering for a number of companies in the south of England. In the early 1950s he arrived at Eastleigh, where he took on the role of chief engineer for the Hampshire Aeroplane Club.

The driving force behind the club was chief flying instructor Viv Bellamy, whose can-do attitude was legendary. The former Navy Seafire pilot had already acquired Spitfire Tr9 G-AISN, ostensibly on the Club’s behalf, adding to a fleet which included Tiger and Hornet Moths, and the last surviving four-engined DH86 Express airliner (for club trips overseas!). In 1957, Bellamy suggested that Currie build two examples of his pre-war ‘Wot’ to the original drawings, to offer lower cost flying to members. Currie supervised a small group which included former Supermarine draughtsman John O. Isaacs and a teenage Rod Bellamy, who continues to work today as a resident engineer at Bodmin airfield in Cornwall.

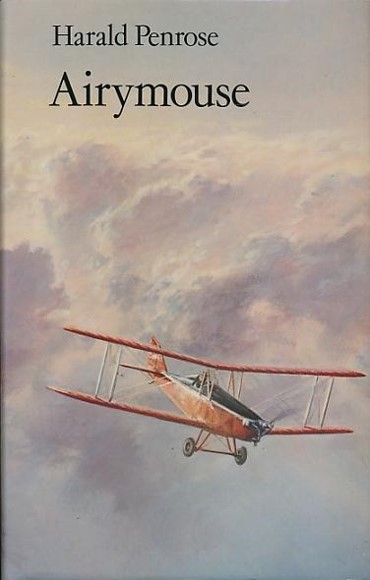

The first of the two aircraft, ‘Airymouse’ gained her name, and greater fame, when she was bought from Hampshire Aeroplane Club in 1959 by Westland’s chief test pilot Harald Penrose, who wanted to recreate the open cockpit pleasures that he’d enjoyed in the early days of his flying career aboard Westland Wapitis and Widgeons. Penrose who had made the maiden flights of aircraft including the prototype Lysander, Whirlwind and Welkin, and test flown hundreds of Westland-built Seafires, was synonymous with the Somerset aircraft maker, but was a proud Cornishman and the Cornish word for Bat, “Airymouse” seemed an appropriate name for the “little biplane of insignificant horsepower” which became his mount for open-cockpit flying adventures, later chronicled in a book of the same name.

Harald Penrose in Airymouse

As with the pre-war examples, Airymouse was initially powered by a two-cylinder JAP J-99 engine of 37 horsepower, but Penrose’s flights were not without incident. On one occasion, Airymouse suffered a fatigue failure of the JAP engine crankshaft, with the propeller disappearing into the distance. That meant a return on to Eastleigh where a former ground power unit 50hp Lycoming was fitted, after a load test which involved a plank across the engine mounts, occupied by members of the Hampshire Aero Club including several Supermarine design luminaries

Load testing for Lycoming engine

With Airymouse as his platform, Penrose explored the Dorset Coast, flew formation on wildfowl above the Somerset Levels and circled ancient British fortifications, describing his view from above in the book he named after the aeroplane. What is less well-known is that one of the things Penrose noted from Airymouse’s cockpit was increasing urbanisation and industralisation eroding the English countryside. It led to him becoming a pioneer environmentalist and a founding member of the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England.

Penrose in Airymouse 1959 Merryfield Peter R March

Penrose flew Airymouse for five years, before selling her to Fleet Air Arm Sea Vixen pilot Stan Hodgkinson who based her at nearby RNAS Yeovilton. The aeroplane next headed north to Sunderland, where Leslie Richardson kept her at Usworth, today the site of the Nissan car factory. Les had a number of ‘adventures’ with the aircraft, culminating in at least one major airframe repair, before the aircraft was stored and put up for sale.

In 1987, Robin Bowes headed north to look at a ‘Wot project’ with a view to using it as the basis of an SE-5A replica to accompany his Fokker DR-1 Triplane reproduction. Thankfully he instantly recognised the aircraft and, having in his youth been inspired by Penrose’s book, elected to restore Airymouse to her original condition.

Much of Robin’s handiwork remains on the aeroplane today, but he flew it for less than a year until, with airshow commitments increasing, he sold Airymouse to Jeff Salter, an air traffic controller working at Belfast International Airport. Jeff sometimes used Airymouse to fly to work from his home in County Down, landing on the grass at the side of the airport’s main runway and parking next to the windsock while he completed his shift. Imagine doing that today!

In 1998, Airymouse recrossed the Irish Sea in the hands of John Dunford. In many ways it was a ‘return home’ for the aeroplane, as his farm was just a handful of miles from Eastleigh where she was originally built. John was another who had been inspired by Harald Penrose’s books and, after some sympathetic renovation by the late Ron Souch, Airymouse had another lease of life in Hampshire skies. Sadly, John began to suffer ill health in subsequent years and Airymouse was used ever-less. By the time of his passing in 2017, the Wot had already been stored for a number of years in a barn on his farm. It was though, the prelude to the latest chapter.

As found by Steve Slater

Like many of its previous owners, Steve was also inspired to fly old aeroplanes by Penrose’s book, so when he heard that Airymouse might potentially be available he just had to investigate further. Steve was invited to the Dunford’s farm to take a closer look, and found Airymouse, dusty, but in surprisingly good condition and stored in a dry barn, albeit next to about two tons of rather acidic ammonia fertiliser which was hardly the perfect storage environment.

After passing an interview from the Dunford family and convincing them he would be a worthy owner, a deal was struck and on 5th January 2018 the aeroplane was derigged and trailered up the A34 to Turweston Aerodrome, creating a fair bit of interest on the A34 dual carriageway!

A good wash saw the aeroplane change colour from dark maroon to scarlet and revealed that the fabric was in better condition than hoped, certainly allowing, with minor woodwork repairs and patches, its original covering to continue (ahead of some more extensive work later this year).

Close Up Susan Stowe

Steve and inspector Alan Turney were more cautious with the engine. The fuel system was flushed to remove some very stale (brown) contents, new fuel pipes and primer were fitted and the carburettor stripped and cleaned. The cylinder barrels were removed from the Continental C-85 for cleaning, checking rings and unsticking valves before ground running could commence.

The engine originally fitted to Airymouse had been the 36hp twin-cylinder JAP, then the 55hp Lycoming, before in the late 1960s a Continental former GPU of about 60hp. This was more recently replaced by a Continental C-85 from a Luscombe. There can’t be too many aircraft that have flown with four different types of engine in their lifetime, not to mention a 250% increment in horsepower!

Airymouse took to the air again on 26th March 2018, in the hands of another who had been inspired by Penrose’s book; the late and much missed Jez Cooke. Steve got his hands on the aircraft for the first time a week later, and as Penrose had written nearly 60 years earlier, found her responsive, “like a spirited pony”. In summary Steve records she’s a delight in the air, but being brakeless and with a fixed tailskid, sometimes a bit wayward on the ground. Not too long ago, with a blustering crosswind taxi, Steve found the only way he could get back to the hangar was in a series of concentric circles, each time getting a bit closer before she weathercocked into the wind again.

Ground handling

There are other bits of aviation history which make Airymouse feel a bit special. The cockpit interior is painted the unique shade of green only otherwise seen on Supermarine aircraft such as the Spitfire and the seat is also alleged to have come from a Spitfire, albeit with the parachute ‘bucket’ rather crudely removed and replaced by a piece of beaten aluminium. You can imagine the conversations at Eastleigh during the original build, “we need a seat, nip up to the stores and see what you can find”! Certainly owning and flying the little biplane is a special privilege and even in the past COVID-ridden year, Steve’s been able to enjoy about 20 hours of open-cockpit self-isolation!

Steve Slater